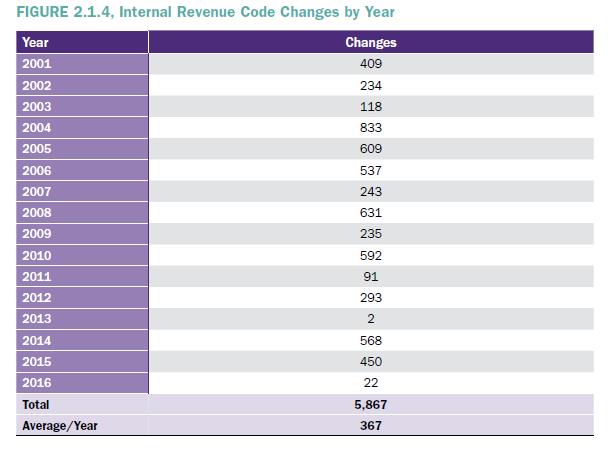

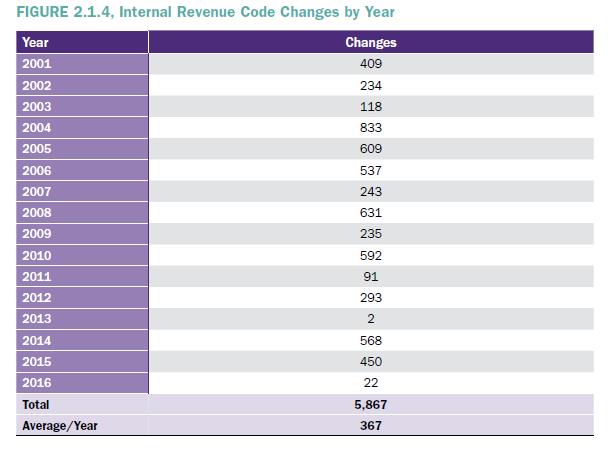

It has now been more than 30 years since Congress enacted the Tax Reform Act of 1986 to substantially simplify the tax code, and since that time, the code has grown more complex by the year, as evidenced by the fact that Congress has made more than 5,900 changes to the code — an average of more than one a day — just since 2001. The compliance burdens the tax code imposes on taxpayers and the IRS alike are overwhelming.

A TAS analysis of recent IRS data shows that taxpayers and businesses spend about six billion hours a year complying with tax-filing requirements. To place this in context, it would require three million full-time employees to work six billion hours, making “tax compliance” one of the largest industries in the United States.

Tax law complexity imposes monetary costs on taxpayers as well. More than half of individual taxpayers pay professionals to prepare their returns, and roughly 40 percent use tax software to assist them, with leading software packages typically costing $50 or more.

Another perspective: The federal government now “spends” more money through the tax code each year than it spends to fund the entire federal government through the appropriations process. In fiscal year (FY) 2016, the Treasury Department estimated that “tax expenditures” (deductions, credits, and the like) amounted to more than $1.4 trillion, while discretionary appropriations were less than $1.2 trillion. Indeed, individual income tax revenue was projected to be about $1.63 trillion in FY 2016. This implies that if Congress were to eliminate all tax expenditures, it could cut individual income tax rates by nearly half and still generate current levels of revenue.

The National Taxpayer Advocate recommends that Congress vastly simplify the tax code.

To achieve comprehensive simplification, tax expenditures would be pared back substantially and the additional revenue would be used to substantially reduce tax rates, leaving the average taxpayer with about the same tax bill he or she has now — but with the ability to compute it much more simply and accurately.

In practice, simplifying the tax code requires important policy trade-offs. For example, Congress historically has allowed married couples and heads-of-households with children to claim larger standard deductions than single taxpayers, thus taxing them less on equivalent incomes. It has allowed a personal exemption for each taxpayer who participates in the filing of a joint return and a dependency exemption for each eligible child, again reflecting a social policy that taxes married couples and larger families less than single taxpayers and smaller families on equivalent incomes. In enacting the earned income tax credit (EITC), Congress on a bipartisan basis created a social benefits program styled as a work incentive, so that only taxpayers who work are eligible to receive program benefits. And on the business side, Congress has provided incentives for research, among other things. In fact, virtually every provision in the tax code was enacted for a policy reason, and it is not l Congress will choose to eliminate all tax expenditures, nor do we recommend that it do so.

However, we strongly recommend significant tax simplification, and to accomplish it, we recommend Congress approach tax reform in a manner similar to zero-based budgeting. Under that approach, the starting point would be a tax code without any exclusions or reductions in income or tax. Tax breaks and IRS-administered social programs would be added back only if lawmakers decide on balance that the public policy benefits of running the provision or program through the tax code outweigh the tax complexity challenges that doing so creates for taxpayers and the IRS.

Factors to consider in making this assessment include whether the government continues to place a priority on encouraging the activity for which the tax incentive is provided, whether the incentive is accomplishing its intended purpose, and whether a tax expenditure is more effective than a direct expenditure or another approach for achieving that purpose.

In addition to suggesting a zero-based budgeting approach to tax reform, we believe the protection of taxpayer rights and minimization of taxpayer burden should be emphasized, along with the IRS’s ability to administer the law. Toward these ends, we have suggested six core principles that should help guide the development of tax reform legislation:

- The tax system should not “entrap” taxpayers.

- The tax laws should be simple enough so that most taxpayers can prepare their own returns without professional help, simple enough so that taxpayers can compute their tax liabilities on a single form, and simple enough so that IRS telephone assistors can fully and accurately answer taxpayers’ questions.

- The tax laws should anticipate the largest areas of noncompliance and minimize the opportunities for such noncompliance.

- The tax laws should provide some choices, but not too many.

- Where the tax laws provide for refundable credits, they should be designed in a manner that the IRS can effectively administer.

- The tax system should incorporate a periodic review of the tax code — in short, a sanity check.

To help guide tax reform discussions — or in the event Congress determines comprehensive tax simplification is not feasible at this time — we identify nine specific areas for simplification. These include:

- Repeal the Alternative Minimum Tax for individuals.

- Consolidate the “family status” provisions (including filing status, personal and dependency exemptions, the child tax credit, the earned income tax credit, the child and dependent care credit, and the separated spouse rule under IRC § 7703(b)).

- Improve other provisions that govern taxation of the family unit, including “joint and several liability” and the “kiddie tax.”

- Consolidate the incentives to encourage savings for education (there are now at least 12 separate incentives).

- Consolidate the incentives to encourage savings for retirement (there are now at least 15 separate incentives).

- Simplify the worker classification rules to reduce disputes over employee-versus-independent contractor status.

- Reduce procedural incentives to use tax sunsets (more than 70 provisions in the tax code are temporary and thus require periodic renewal).

- Reduce income phase-outs, which affect roughly half of all returns each year and add considerable complexity to tax computations.

- Streamline the penalty regime for tax violations (there are now more than 170 penalty provisions, up from 14 in 1955).

According to a tally compiled by a leading publisher of tax information, there have been almost 5,900 changes to the tax code since 2001, an average of more than one a day.

Read the full recommendation